Reflections on ‘Home’ from Tulsa and Fresno

By Priya Prabhakar, REP-SF Organizer | October 9, 2025

In April of this year, I learned about the Cherokee concept of wellness – of ᏙᎯ – tohi. It’s not just the absence of disease, but it’s a smoothness of life, a peaceful existence, an unhurried pace, and an easy flow of time. It is a form of collective health, rooted in harmony of the body, mind, heart, and spirit.

These days, I think about how distant that way of living feels. We live under systems that make us ill. Our basic needs are exploited for profit, our attention is fragmented, and crisis is the norm. Yet, I remind myself that tohi is not just a destination. It is an orientation towards the world. By creating meaning in relationship to each other, we can heal and create new worlds that bring us closer to a collective embodiment of tohi.

This year in April, I had the opportunity to visit Tulsa, Oklahoma for the Spatial Futures Fellowship (SFF) Convening hosted by PolicyLink. In August, I visited Fresno, California for the Queer Housing Summit (QHS) hosted by the South Tower Community Land Trust (South Tower CLT). Jason Wyman / Queerly Complex, Elliot Bailey, and I were co-curators of the More Than Mere Existence art exhibition at the QHS. These in-person gatherings nourished me with conversation, imagination, and connection with organizers and artists all around the country, working towards the same horizon of spatial, housing, and land use justice.

Tulsa is a city with deeply intertwined Black and Indigenous histories, home to the Muscogee, Cherokee, and Osage Nations, and to the Greenwood District, historically known as ‘Black Wall Street.’ Over three days, the SFF cohort learned of Tulsa’s history and present, shared experiences of community organizing, unpacked the violent mythologies that have propelled spatial injustice, and reckoned with the weight of what has been lost.

Four months after Tulsa, I visited Fresno. South Tower CLT is a community land trust led largely by queer and trans residents. It offers a model of home beyond the speculative market. More Than Mere Existence was born from an anti-curatorial call for art, rooted in queerness, not just as an identity, but as a political orientation. One could submit if they were: 1) trans or queer, 2) connected to the struggle for spatial justice, and 3) submitted existing work. This generated a network of 42 artists who showcased their art physically during the Summit, and digitally, archived for future generations.

Both trips echoed a vision at the heart of our work at the Race and Equity in all Planning Coalition (REP-SF) – a shared commitment to building a home that serves the collective. San Franciscans know too well the forces that unravel a collective sense of home. From the genocidal conquest of the Yelamu, racist exclusion of redlining, destruction of neighborhoods through redevelopment, evictions of the tech boom, homes lost during the subprime crash, to the ongoing churn of gentrification. Since our coalition came together in 2020, REP-SF has fought the current iteration of these forces – the market-driven policies of the Housing Element, which mandates housing production over the next eight years. While REP-SF’s work has led to the inclusion of dozens of equity-based actions, the Planning Commission recently approved Mayor Lurie’s upzoning plan (“Family Zoning Plan”). This plan completely ignores decades of community expertise. It threatens low-income communities of color with a rollback of tenant protections, the displacement of small businesses, public site giveaways, and no funding for the affordable housing that San Franciscans so desperately need.

As our coalition and communities prepare for the impacts of upzoning, I want to share three reflections drawn from my experiences in Tulsa and Fresno:

Each community has a unique struggle for self-determination, all shaped by the same forces of displacement.

Community expertise means using the stories, experiences, and histories of ourselves and our communities to drive our analysis and theory of change.

The survival of our movements depends on proactively building homes, systems, and worlds alongside resisting threats of displacement.

Each community has a unique struggle for self-determination, all shaped by the same forces of displacement.

Artwork by Yesenia Veamatahau for More Than Mere Existence

“I’ve seen how every day those of us who were born and raised in the Bay are surveilled, disposed of, and pushed out. And yet, we live.”

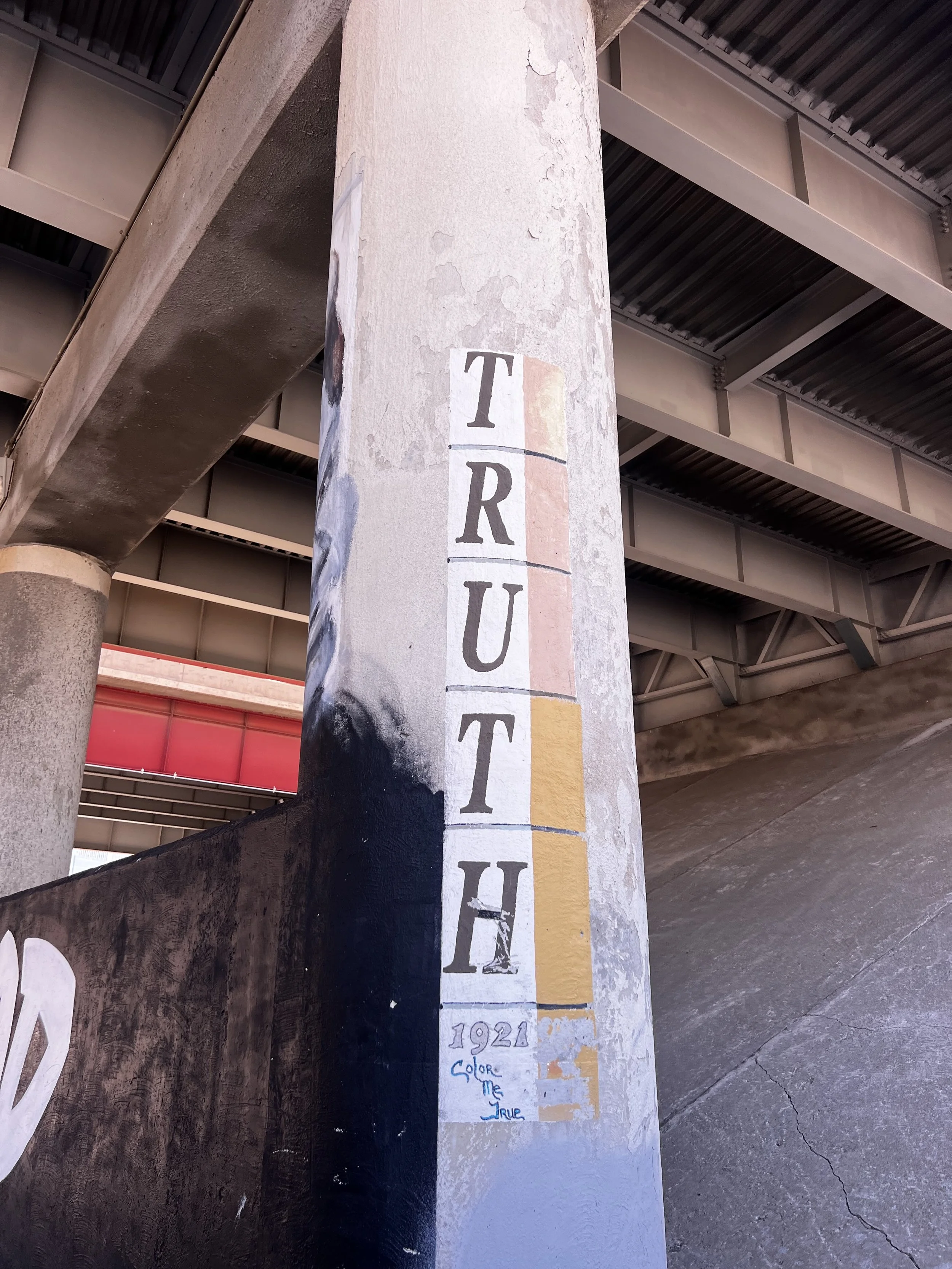

Under the I-244 Highway, which cuts through Greenwood (Photo by Priya Prabhakar)

In the 1950s, the construction of Highway 99 in Fresno, the Central Freeway in San Francisco, and Interstate-244 in Tulsa tore poor Black families, homes, and neighborhoods apart by design. Each city used the same playbook – racist dispossession codified into law in the form of the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act. Self-determination is the right of a community to envision, build, and choose its own ways of life in relationship with each other and the land. On my trips, I saw how unique stories of self-determination emerged from the same forces of displacement.

My cohort and I walked the streets of Tulsa, led on a tour by historian Chief Egunwale Amusan. At one stop, he asked us to close our eyes and step back in time to 1921. Historic Greenwood: one of the most prosperous Black neighborhoods in the country, stretching nearly a mile in each direction. Amidst Jim Crow segregation, Black Tulsans had built a world of their own, a walkable community of over 10,000 people and 191 businesses – restaurants, grocery stores, doctors, lawyers, tailors, theatres, bars, and more. Kristi Williams, whose great-aunt Janie Edwards once lived in Greenwood, described the community as “an economy within an economy, a nation within a nation, a city within a city.” In Greenwood, every dollar recirculated more than 30 times, weaving together a fabric of mutual care that allowed Black life to flourish as a survival mechanism under the violent weight of white terror. When I opened my eyes back up, more than a hundred years later, I saw the overbearing I-244 highway upon an empty neighborhood where there should have been people.

Chief Egunwale Amusan, historian and owner of The Real Black Wall Street (Photo by Priya Prabhakar)

A thriving Black township that created a safe home through economic and political self-determination was a threat to white order. On the night of May 31, 1921, more than 10,000 white Tulsans, deputized by law enforcement and the government, burned down and looted homes and businesses in Greenwood in a military-style attack. Airplanes circled, dropping turpentine balls. More than 300 Tulsans were murdered, their bodies carelessly dumped in the Arkansas River. Over 700 Black Tulsans were injured, and over 6,000 residents were sent to internment camps following the destruction of their homes. It took the City of Tulsa 104 years for the Department of Justice to launch an investigation into the massacre and excavate the unmarked graves of those who were killed – the majority of whom have still not been found and are unable to receive dignity in their death. The survivors of the massacre still have not been paid reparations for the wealth, lives, and dreams destroyed. The land holds forgotten histories of those who had built a home of cooperative economics and collective responsibility in dispossession.

Grace, Love, Desire by Trayvon Smith for More Than Mere Existence

“Grace, Love, Desire”

In his piece, “Grace, Love, Desire,” artist Tray Smith mediates on the quiet power it takes to love yourself out loud while being Black in America: “As a Black creative, expressing love for myself, my softness, my strength, my queerness – is a radical act.” As queer people, we often have to forge our paths with no blueprint as a result of rejection from the homes we were born in. At South Tower CLT, I witnessed queer self-determination, building a structure to keep housing affordable for those who disproportionately experience housing precarity. Forming kinships and networks of proximity is a survival mechanism.

Another survival mechanism is creative expression – a way to build new worlds. Before living it, we must imagine it. The radical imagination required for self-determination echoed through the art in More Than Mere Existence. Michelle Feng’s piece, for example, imagines a world “rooted in Sino-Eastern futurism and traditional ecological knowledge, while drawing inspiration from modern Solarpunk themes.”

Artwork by Michelle Feng for More Than Mere Existence

Community expertise means using the stories, experiences, and histories of ourselves and our communities to drive our analysis and theory of change.

Steps to Nowhere in Tulsa (Photo by Luis Oyola)

While radical imagination can allow us to form a relationship with our future, storytelling is a way to preserve and share our past and present. As Chief led us around historic Greenwood, he held up laminated photos taken a century ago, building a historical tapestry of Greenwood, woven with the stories of its residents. Midway into the tour, Chief showed us sets of concrete steps leading up to empty expanses with large trees and small patches of purple periwinkle flowers – steps to nowhere. I learned that these plots of grass once had the family homes of Greenwood residents destroyed during the massacre.

Despite being born and brought up in Tulsa and a descendant of three survivors of the Tulsa Race Massacre, Chief had only learned about the history of Black Tulsa when he was 18. The experiences and knowledge of what his ancestors both built and lost were denied to him by institutions and dominant education systems. Learning these stories led him to dedicate his life to The Real Black Wall Street – a family-run business “committed to telling the history of Greenwood from the perspective of its descendants and survivors.” One of Chief’s quotes has stuck with me: “Head comes before book.”

At the Queer Housing Summit, storytelling was an integral mode of knowledge-sharing and world-building. In More Than Mere Existence, artists expressed their lived experiences of spatial injustice through stories, poems, paintings, and photographs. KB Brookins, a speaker at the QHS spoke of this as a matter of survival: “Archiving queer and trans histories saved my life.” During these trips, I witnessed the vast potential for change in storytelling. Together, we create a rich tapestry of community expertise and knowledge that comes from the bottom up, not fueled by those who exploit misinformation and misleading slogans as a means to their ends.

The survival of our movements depends on proactively building homes, systems, and worlds alongside resisting threats of displacement.

“It wasn’t always this, and it won’t always be this. How can I find the most liberated position in the current reality?”

In these moments, I think about all the stories we do not get to hear: of communities being terrorized by US-funded bombs, the genocidal Israeli occupation, ICE, and the free market. Those who do not have the luxury of calling somewhere home, while the market and militarism hold homes and land captive. Instead of affordable housing, money is being poured into more market-rate and luxury housing, the police budget, and surveillance technologies. Mayor Lurie’s upzoning plan gears up for the escalating wave of gentrification with the AI boom, which will raise rents and displace, yet again, low-income communities of color.

From my visits to Tulsa and Fresno, it’s clear that these moments require us to both fight to protect our communities from home demolitions and defend rent control and tenant protections, and we also must invest in building alternative systems through research and land-banking to develop community spaces and homes off the speculative market. How can we collectively take matters into our own hands, without waiting for the permission of politicians or developers? How can REP-SF build pathways for community members invested in neighborhood fights to join in citywide organizing efforts to advance the funding and infrastructure of alternative economic systems? How can we use storytelling, narrative change, and popular education as an alternative to corporate media that bows down to tech billionaires? On both trips, I learned that prefiguration is a key part of the struggle for self-determination. Prefiguration means building a new society “within the shell of the old.” The Greenwood District and South Tower CLT represented different versions of building liberatory homes within systems hostile to your communities’ survival.

In a recent SFF session, Dr. Ted Jojola, Director of the Indigenous Design + Planning Institute, gave a talk about an Indigenous framework that guides planning towards a seven-generations model: Imagine you’re the middle generation: honoring the ancestors who brought you to where you are now and working towards the sustenance of the next generations. How can we fight to restore balance and health to our communities by creating alternatives to these systems of dispossession, exclusion, and theft? What can we do today such that tomorrow we can do what we cannot do today?

More Than Mere Existence: A Nothing New Catalog & Virtual Gallery/Exhibition

queerlycomplex.com/mtme-catalog

Designed by Hamza Kubba

More Than Mere Existence is an exhibition and a catalog, physically and virtually. It gathers and showcases Trans and Queer Artists fighting for housing, land use, or spatial justice. Forty-three artists submitted works, including REP-SF members! It is a testament to the power of art as a means of self-expression and as a way to bring people together across generations, cultures, identities, and distances.